Future Apple project engineer, John Couch was among the first graduates of Berkeley University's computer science program, and was immediately recruited by Hewlett-Packard to work on the HP-3000's software. Couch recalled a conversation with company co-founder Bill Hewlett:

I remember Bill telling me, ‘We did market research on a calculator - all it did was multiply, subtract, add and divide - using Reverse Polish Notation', and they came back and said ‘Don't build it, nobody wants it’,' and Bill said, ‘I want it and furthermore, I want to be able to put it in my shirt pocket.’ We built and introduced the HP-35 for $395, and straight away, it was doing 180 million dollars of annual revenue.

The HP-35 was Hewlett-Packard's first pocket calculator.

The largest slide-rule company in the world, at the time, was suddenly out of business because they thought of themselves in the slide-rule business, not the computational business. That's a mistake a lot of people still make to this day.”

Couch later connected with an equally decisive cofounder.

Also headed to HP was future Apple engineer Ron Johnston:

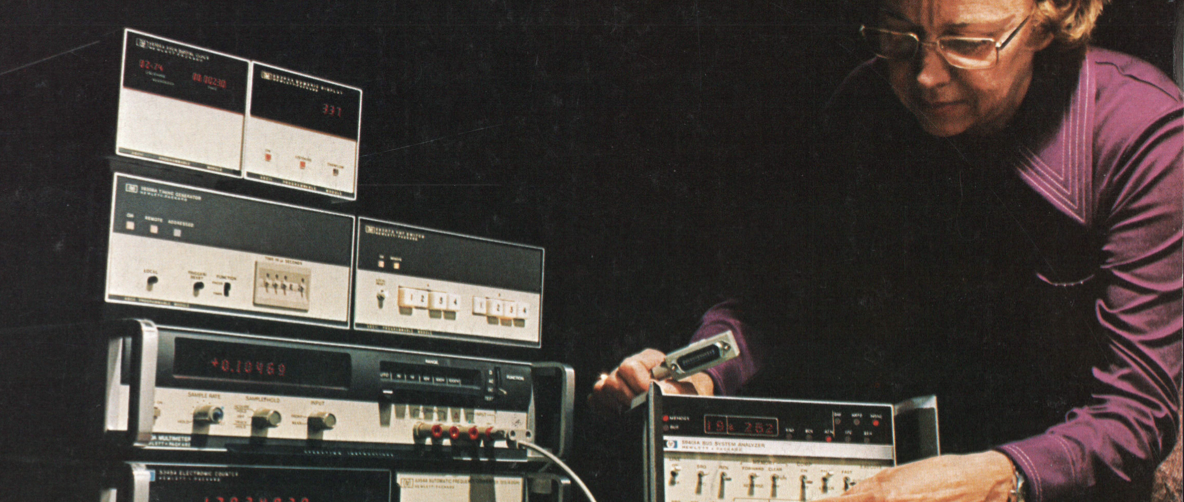

My parents are hardworking people, but they couldn't afford to put me through college, so the engineering development program at Point Magu was an answer to prayer, and I was able to support myself as a freelance programmer from everything I learned there. As I finished my degree, I worked part-time as a programmer at UC Davis and UC Santa Barbara. Then, I got recruited to HP Labs in Palo Alto. I was so blown away that the people who interviewed me were the guys who had developed the HP-35 pocket calculator. The reason that it resonated for me is that the HP interviewer who came to the UC Davis campus had given me an HP journal that detailed the HP-35 team. I knew their story, their names. So when I showed up for my interview, and it's those guys—Klock, Rode, Whitney—I'm thinking, my gosh, why would they ever hire me? They know so much, and then they said to me, ‘We don’t usually find new college grads who have the years of experience that you have', so they gave me a job. I suddenly became a Junior Engineer with access to an HP-2100 computer. HP Labs was modeled on Bell Labs, where you experiment and expect to learn maybe 20% of the time. There was no mechanism for labs to productize anything, nor manufacture anything. But you learn stuff.

HP also had a "next bench" concept which meant engineers could tinker with ideas at the workbench next to their assigned projects. Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard famously kept labs and storerooms unlocked so engineers could experiment with components on nights and weekends. A young HP engineer had instead built something in his apartment. Johnston recalls:

HP had a company-wide system in those days where you could work on projects that you thought HP may build. You could use their equipment, parts, and resources in your downtime. The only rule was that HP had the first right of refusal on it. Every month or so, an employee would come forward to present their idea. A young engineer from HP’s calculator division, APD (Advanced Products Division), let us know he had something to present. So he comes in and takes a seat opposite the four of us from around HP. He has some drawings, and he's describing a single-board computer concept. We were all engineers, and so we gave him his time and then asked him, ‘Steve, how do you get stuff into this thing? And how do you get it out? He replied, ’Well, I haven't worked on that yet.' Then we asked, ‘How do you get it to display anything?’ He replied, 'Perhaps a television, I haven't worked on that yet.”

The young man later told author Jessica Livingstone:

“I thought that they (HP) deserved it first. And I wanted Hewlett-Packard to build this. I loved my division. I was going to work there for life. It was the calculator division; it was the right division to move into this kind of computer.”

Ron Johnston continues:

“Well, the four of us had a quick discussion and advised the young engineer, 'Thanks, but this isn't anything HP is going to build, so you're free to go with it. And it's yours. Of course, he did. Steve Wozniak managed to hook up with Steve Jobs and make a real computer out of it.

Excerpt from https://books.by/john-buck/inventing-the-future